Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

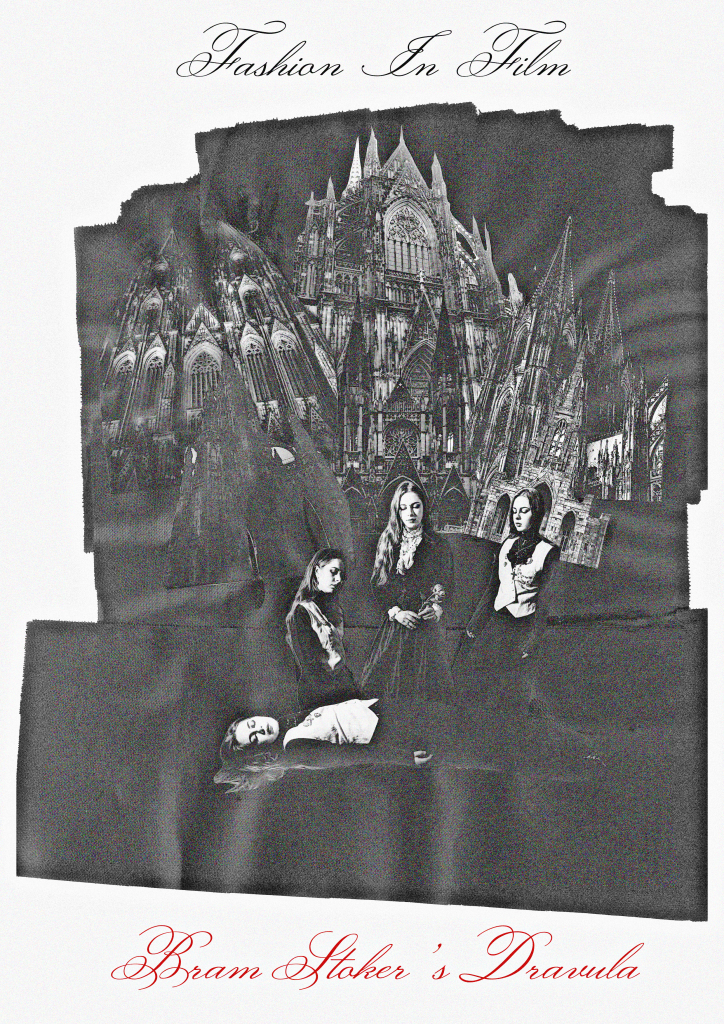

Collage created by Rida Shah with their own photography, exploring vampiric styles and their correlation to the Japanese subculture of Ouji Kei

Looming towers, bathroom doors with axe marks by a wild janitor and kitchen tables for family dinners; all integral sets to a film’s storyline. Yet, in 1992 director Francis Ford Coppola and costume designer Eiko Ishioka broke this code with their blood sucking production ‘Bram Stokers Dracula’ where according to Coppola ‘the costumes are the set’.

Before we get into the costumes used in this iteration of Dracula lets go back in time and discuss a fashion archetype of vampires in film that makes Coppola’s so unique. All depictions of vampires have something about them that separates them from humankind to create an otherness among them, even those that are trying to blend in. From pale skin to red eyes and abnormally long fingers like archaic depictions of Greek Gods vampires are never as dull as their human counterparts.

So, in 1983 Tony Scott directed a vampiric film named The Hunger it subverted the formal style of vampires like Nosferatu and featured fashion trends from the 80s such as sleek leather blazers, big shoulder pads and new wave sunglasses known as the Bauhaus movement featuring looks from Yves Saint Laurent. Making the vampires like humans yet still opulent, stylish and aspirational.

Some 18 years later the costumes influenced Alexander McQueen’s 7th collection fittingly named ‘The Hunger’ which featured translucent body moulds, extreme cutouts and sharp lines. In Queens’ other works such as ‘The horn of plenty’ collection this inspiration can be spotted once again with the use of pale skin in the makeup, blood red lips and a silhouette that paralleled that of the poster of the hunger.

Whilst Scott depicted contemporary couture, Coppola and Ishioka broke boundaries vampires weren’t ‘trend hoppers’ or boring men in suits anymore they were romanticised and fantastical with huge flowing cloaks, silk and satin blouses and heavily bejewelled garments. One aspect to note is how Dracula came in so many forms as Ishioka stated in the film’s documentary ‘my image of Dracula should have a million faces’ ‘almost like an endless transformation’.

One form is Dracula in a younger body meeting Mina he’s wearing a frock coat, tight fitting and calf length paired with a waistcoat and top hat, normal for a man of the 19th century but he’s also wearing sunglasses and has shaggy long hair symmetrical to a crude rockstar like Ozzy Osborne creating this atmosphere of satanic panic.

Another is his suit of armour resembling a wold it transforms into yet another common motif of the film. The suit has ribbed pieces giving the impression of human anatomy acting as a reflection of how Dracula gains all his power; flesh. Just as the armour does many of the costumes used for the vampire’s act as a direct contrast to their mythological nature. Both the armour and Lucy Westenra’s wedding gown, which acts as a reflection of white purity, bears huge lace collar which Ishioka says was inspired by a lizard.

Now! Let’s put this article to rest by discussing Dracula’s resting gown which was inspired by the gold of byzantine art. The patchwork of gold and silver emulates an ‘accumulation of lives’ a fitting way for an eternal being, who ate the souls of many, to say goodbye.